The recent silencing, for maintenance reasons, of the bell known as Big Ben met a suitably muted response from the nation. A half-hearted effort by a handful of MPs to lend the moment significance faded on the wind. But, on the day the last chimes rang across Westminster – and the small group held their vigil outside the Big Ben tower – it seems that inside the Houses of Parliament, a disruption may indeed have been felt.

The following is a thread leaked by a member of a messaging app group consisting of trainee political journalists (names have been removed and messages re-ordered for coherence):

A: HOU and TOOP making themselves known today.

B: fuck yeah

C: Decidedly odd in the lobbies

B: ‘Decidedly odd’ is a typo for ‘fucking weird’ right?

D: Old wives tales now? Are all hop groups as hot as this one?

A: Haven’t seen you around today?

D: At home working on a piece. So?

B: So stop wanking sorry working on your piece and come see for yourself

A: You do kind of need to see what it’s like.

E: I take it you guys are willing to break this story? If not maybe keep it offline?

Brief. But the thread hints at a contemporary resonance for a set of phenomena portologists had thought purely historic. Phenomena that, in some cases, go back centuries, and have come to be known collectively as The House of Uncommons and The Other Other Place.

Here are just a few examples:

Lord Alconbury Incident

For several years at the beginning of the 20th Century, the Lords’ Chamber had a gardening problem. A strange plant would grow from beneath the benches along which debating peers sit. Botanists were perplexed – at a loss not only as to how the plant should be categorised, but as to where it was coming from, and how it might be stopped. The vine-like tendrils were tough, sticky and caused painful rashes and bruising to unclothed skin.

Palace staff, armed with gloves and secateurs, did their best to keep on top of it – a risky and unpopular business, the main result of which was that the mysterious weed grew back stronger. On hot and humid days, it grew so fast that the sound of stamping feet almost drowned out debate, as sitting peers attempted to keep the tendrils at bay. Consequences if they failed to do this could be serious, as demonstrated by the ‘Alconbury incident’ of 1912.

Witnesses record that Lord Alconbury was spending the afternoon as he often did: by sleeping off his claret-sodden lunch while peers debated in the House around him. His slumped figure, gradually disappearing from view behind the benches, did not attract much attention. It was only when it came time to vote on the matter at hand (an act concerning governance of India), that someone thought to give Lord Alconbury a nudge – at which point it was found that several thick tendrils of the vine had wrapped themselves tightly around his left leg. Worse than that, the Lord appeared to be being dragged into a ‘diabolical fissure’ which had opened where the bench in front of him met the floor.

When, after great effort, clerks wrestled his leg back from the tenacious vine, his trousers were in rags, and bruises and sores covered his skin. His foot – when it was retrieved from the strange opening – was lost entirely to some kind of ‘accelerated putrefaction’. It was later amputated.

The extent of the problem during the First World War is unknown, records not being kept. But by the time of that conflagration’s end, outbreaks of Alconbury’s Curse – as the plant came to be known – appear to have died down.

The Monstrous Chamber

The Commons Chamber was rebuilt in 1945, having burned down during the Blitz. It is unknown whether these events have any bearing on the chamber’s shaky dimensional footing during the mid-to-late ’40s, but many scholars find the timing persuasive. Throughout those years the newly-built walls and ceiling would shimmer as if seen through heat – sometimes disappearing entirely for a moment, to reveal another, far more vast interior, in which darkly Gothic galleries ascended dizzyingly. (Less often, a vision of an ‘infinite cosmos’ faded in and out around the MPs.)

It was convention among members of the house that the phenomena, if occurring during a debate, should be ignored. This convention seems to have been observed, with the notable exception of Douglas Clifton Brown, the Speaker of the House. Hansard records him loudly admonishing the ‘monstrous chamber’. More regularly – and famously – he would interrupt the flow of debate to implore the walls around him to, “Hold fast! Hold”.

The Delphi Committee

It is the 1960s, and an elite club of Tory MPs meet in secret to discuss ways to influence party policy, and better combat the ‘socialist threat’. So far, so unsurprising. Until you learn of their meeting place.

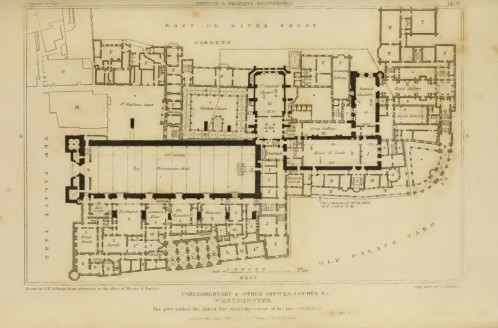

Behind a panel somewhere in the corridors leading to the whips’ offices, there is a door to a silent and unpopulated cityscape, where wide piazzas are bordered by gleaming white columns, and great blank pediments tower over shadowy porticos. There are no clouds in the sky, and no sun. A strange light illuminates the place.

According to the unpublished memoirs of one former member, the practice came to an end when longtime members began to show signs of what they named Delphi Decay, a strange discolouring and weakening of skin, teeth and hair. Until then, he writes, nobody seemed to know or care what the place was – or how the gateway to it had opened. But the secrecy emboldened them: “I balk, in the mellowing of my dotage, at the hate-filled schemes proffered to those unearthly, echoless piazzas; to that deathly, breezeless air”.

Time Anomalies of The Not Content Lobby

The Not Content lobby – a dark, oak-lined corridor to one side of the Lords’ Chamber, which peers walk through to register their disapproval of a motion – has a habit of living up to its name. Various phenomena are associated with it, in particular a series of ‘inverse’ time anomalies. In 1840, a group of peers, voting on a tabled amendment to the wording of the fisheries convention where it related to the United Kingdom’s standing with France, thought they had spent ten minutes in the lobby. To those outside, however, the peers went missing for a full 24 hours. The subsequent effect on the result of the vote (peers are counted on leaving the lobby, and in this case had done so a day too late), led to a convention whereby the lost votes of ‘slipped’ peers – ie peers who were seen to enter the lobby but not depart it within a ‘natural’ timeframe – would be balanced out by ‘pairs’ in the Content lobby surrendering their votes.

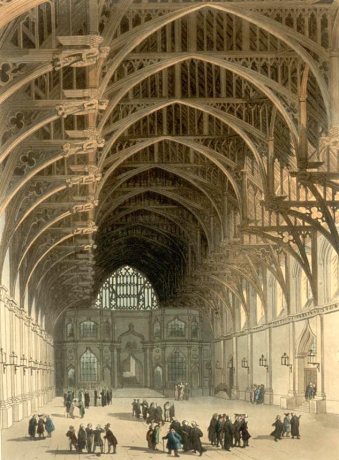

Westminster Hall ‘raftergheists’

The celebrated, seven-centuries old hammerbeam oak rafters of Westminster Hall have been troubled from time to time by spectral breaches. Henry VIII would apparently stand and shout obscenities at the shadowy figures which writhed above trials held in the Hall. Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate of 1653 to 1659 was particularly troubled by them – attempts by an exorcist to animate the ceilings’ carved wooden angels in order to combat the ghosts were unsuccessful.

The Shadow Tower

The speculative fiction of a bored employee? Or an account of one man’s inter-dimensional experiences? Whichever side you fall down on, the diaries of William Pewter are well worth a read.

Pewter was a lamplighter – it was his job, during the last years of the 19th century, to work through the night to keep the gas lights that illuminated the clock faces of the ‘Big Ben’ Clock Tower lit. He recounts that after checking the lamps, he would descend the 334 steps from the belfry down to ground level, and enter a hidden door that led to another 334 steps – down which he would descend into ‘that dread catacomb, the inverted shadow Tower, directly beneath our proud beacon’.

Pewter doesn’t describe the strange ritual he carried out – nor whatever entity or entities compelled him to do so – save to say that it had the outcome of rejuvenating the ‘unearthly glow’ of the ‘hideous insults’ that were the shadow clocks, with their strange symbols in place of numerals.

At times he hints at a larger structure beyond the shadow tower. One passage has become well known to those who study London’s vulnerable dimensional boundaries:

“Dark parliaments whisper in the walls of this place. Dread representatives of night-wreathed boroughs stalk the very shadows. The strong-hearted have nothing to hide. But the venal should know this: the mistruths and obfuscations spoken in this place are breath and blood to the hidden ones, who descend with your black words to their own cursed House to twist and weave them into ever darker meaning in the service of their demonic legislation”.

The later pages betray an increasingly haunted man. In October, 1899 – two months before he died, aged 38, of unknown causes – he wrote of being harrowed by “those great monsters, the shadow bells, tolling ceaselessly in the darkness and deep within me wherever I turn”

The centuries have seen many notable phenomena and countless minor discrepancies. But there was little sign of dimensional disruption when PoL visited the Palace of Westminster recently.

Not that our trip was wasted. In the crypt-like visitors’ cafe we met a friend of ours, Susan Macks, Professor of Gateways and the Multiverse at the University of Connecticut, and a leading expert on London’s interdimensional gateways.

Over flat whites and triple-chocolate muffins we got her thoughts on a key debate surrounding the Westminster phenomena. Do the events constitute evidence of ‘shadow’ entities – that is, another Palace (or Palaces) of Westminster, existing in separate dimensions but somehow temporally or metaspatially linked with our own? Or do the various accounts of gateways, anomalies and untetherings share a more tangential connection?

“Oh, put me in the dimensional shadow basket. Hell, yes. Seriously, quote me on this: House of Uncommons is not a catch-all. The Other Other Place is not an umbrella term. The Pewter text is key here, right? There’s something else there. Has its moments, take its holidays, comes and goes. Manifests in a heap of different ways. But it’s there.”

She smiles.

“And yes, I know this throws up a whole load of questions. And no, I don’t know all the answers”.

Susan has to fly. She says she’s busier and busier in London these days. But we manage to keep her chatting a while longer.

She talks about Westminster in general. She is drawn to the area’s origins as an island, surrounded by fens, where the Tyburn split to join the Thames. Some say the road out west forded here, since Roman times and before. There may have been a place of worship where the Abbey now stands long before records begin in the 10th century.

And we talk about ‘Westminster’, the metonym. The word that describes a place, a system, a community, an establishment, a club. A by-word for democracy that is also an end to discussion. An answer. A means of wielding power, and of ceding it. A beacon. A facade. A hope. A lie.

“I’ve been waiting for this doozy to come back”, says Susan, as she reaches for her jacket. “If what your young reporters are hinting at is true, well – I better clear some space in my diary.”

- Candidate: The House of Uncommons and The Other Other Place

- Type: Various

- Status: Historic (pending review)

The featured image is taken from The Fugitive Futurist (1924) by Gaston Quiribet

I’ve just stumbled on this site today and it is brilliant!! I love the interweaving of the real and unreal until the boundaries blur. Fantastic work.

LikeLike

Thank you very much! Glad you like it.

LikeLike

Superb characterization of a place of democratic legislation.

LikeLike

Why can’t Susan Macks be found on the University of Connecticut website?

LikeLike

Multiverse security

LikeLike