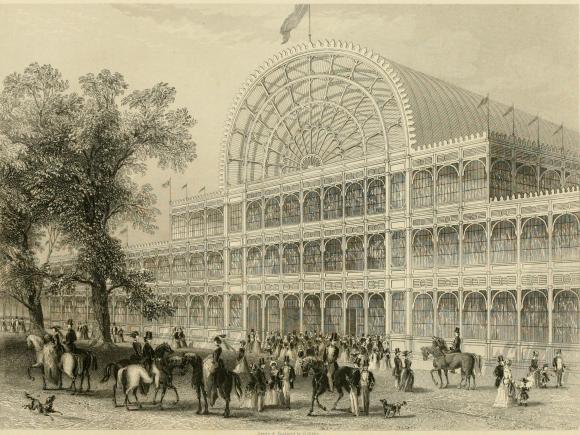

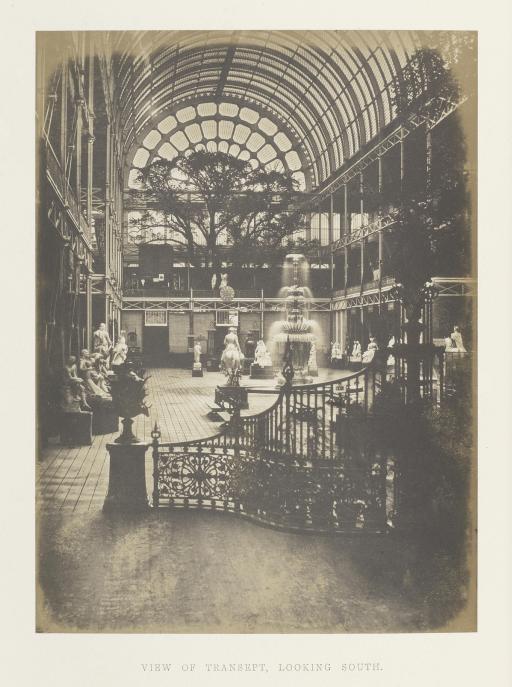

A giant shop window, a flashing of the spoils of imperial conquest, a chance to position monarchy side by side with social and commercial interests: The Great Exhibition of 1851 was many things. Officially, the world fair – opened by Queen Victoria and housed in a vast Crystal Palace of iron and glass in Hyde Park – was a showcase for advances in global industry, arts and sciences. Even at the time it had its critics (Prince Albert only got behind it once he was sure the idea was popular), and post-colonial historians have found endless layers of meaning to this crashingly unsubtle declaration of global power.

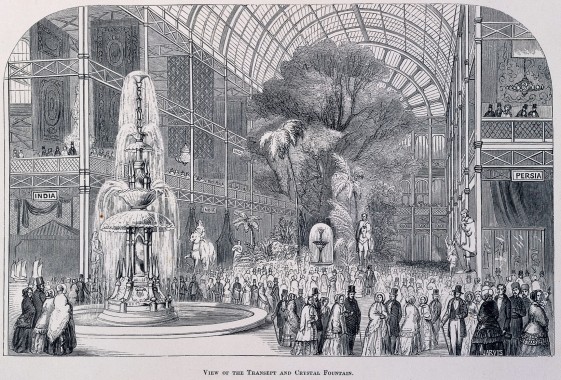

One thought that might have occurred to your average 1850’s Londoner, as they filed slowly past the parade of statues, jewels and stuffed elephants, was that the Great Exhibition was busy. An average day saw over 40,000 visitors, more than twice the number that the British Museum sees today. On one October day, that tally reached over 100,000. With such numbers, it’s easy to see how a small tear in the dimensional fabric could have gone unnoticed by most punters. When a portal opened one Saturday afternoon, it was witnessed by only a handful. Add to that what may have been a conscious effort to keep news of the breach spreading, and frankly we are lucky to have a story to tell at all about what has come to be known as the Crystal Palace Stardoor, or more commonly, the Vacuum Sugar Event.

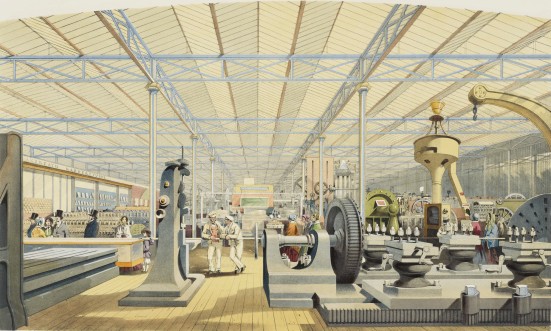

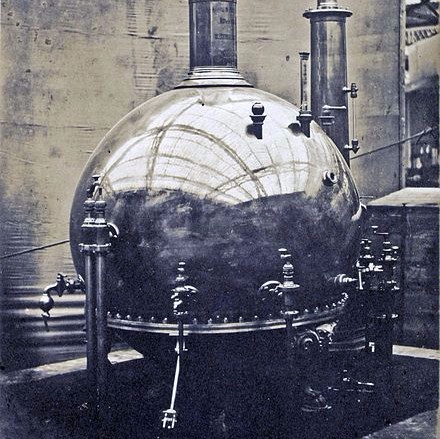

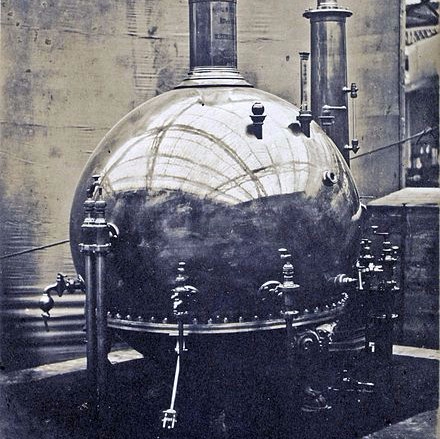

William Canter had booked his stall at the Exhibition in order to show off his patented vacuum apparatus, a device to enable liquids to be boiled at lower temperatures. (The invention was particularly aimed at the sugar industry – the potential for cutting fuel costs when boiling sugar cane was good news for the profits of plantation owners).

Tucked away in a corner, off the main gallery, Canter was a few minutes into an afternoon demonstration when he heard an unusual pop from inside his machine. Soon afterwards, something strange started to emanate from the large spherical apparatus.

“Some manner of darkly coloured smoke”, Canter recalled later. “My first thought was ‘Blast it, the sugar cane’s burning’. My second (and almost simultaneous) thought, was ‘How on earth can that be?'”

Martin Bull, a cab driver by trade, recalled the moment. “It didn’t look like any smoke I ever saw. Black as pitch, it was. But it moved more slowly than smoke. The stuff came seeping out of a valve in the machine and sort of hung there, a few feet off the ground. Like a little dark cloud. Then I noticed the lights”.

The “lights”, as Patty Granger, a nearby flower-seller, quickly recognised, were celestial in nature. “It was like a patch of night sky, really. But the most glorious night sky you ever saw… great swirling clouds of stars…The closer you got to it, the more of the night sky you could see. Like a window, if you get my meaning? The really strange thing was, when you walked round the back of it, you could see stars going the other way”.

Many of the witnesses recall getting close to the stardoor to get a look at the wonders that opened out beyond it; none of them, when they were tracked down years later, could forget the man and woman who got too close.

They all retold the moment. Accounts speak of a well-dressed couple, who may or may not have been connected to the sugar trade. The man was bullish and self-important, loudly insisting that they should stand closer than anyone else. The woman seemed reluctant at first, but, perhaps emboldened by her husband’s attitude, she soon made a dreadful mistake. Declaring that she’d like to see the stars beneath their feet, she craned her neck so that her entire head reached beyond the threshold of the opening.

The terrible, strangled sound which filled the air proved hard to describe for most witnesses. Some said it was not human, some said they thought the glass panes were falling in, one was sure it was the sound of screaming, and said that though it was loud it was “fractured, like a cry heard across a stormy valley”. Many said the sound seemed to come from all around them, and expressed amazement that the whole Exhibition hadn’t heard it. Interestingly, one witness said that she’d experienced a prolonged flash of brilliant light, and only afterwards began to think of it as a sound.

After the initial shock, people rushed to the woman. By the time they had pulled her back across the threshold, her fur hat and shawl had gone. Some recall a glimpse of strangely matted hair and wide, black eyes set in a bone-white face, before the woman’s husband threw his jacket over her and hurried her away into the crowds. They have never been tracked down. Canter later said he was amazed not to have heard from their solicitors.

Those still surrounding the stardoor now had a new problem. Someone noticed that while the size of the portal had initially stabilised, it was now growing again. This threw the small gathering into a panic. What if it didn’t stop? Canter himself tried desperately to tinker with his machine, thinking that somehow if he could reverse its process, the thing might be sucked back in.

Some tried to help him, some began to turn and walk rapidly away, but then, just as Canter was about to run out of ideas, there was another sudden POP, and the stardoor snapped shut.

Canter recalls a moment in which “it seemed to me as if the whole of the Crystal Palace fell silent, although of course it was only our little corner”. But the silence in Canter’s little corner was broken by something unexpected: applause. It appeared that many in the small crowd had decided that it had all been some elaborate entertainment, and they soon dispersed into the great hall around them. Canter packed up soon after, and withdrew from the exhibition the next day.

It’s unclear exactly how high up news of this event reached. Canter and the other witnesses were tracked down years later by a civil servant, and the interviews remained classified until very recently. Someone must have made the initial report. What does seem clear is that a decision was made to keep news of the phenomenon from Prince Albert, the Exhibition’s great patron. To PoL’s mind, this presents an intriguing ‘what if?’. Prince Albert was keen to position himself as a champion of scientific progress. The Victorian Movement didn’t really get going until after Prince Albert’s death. What if he had learned of the stardoor, and with his support the 19th Century interest in portals had peaked twenty years earlier? Would the Movement have retained its momentum to a greater extent than it did? If it had, we might be living in a very different base reality today.

- Candidate: The Vacuum Sugar Event

- Type: Stardoor

- Status: Historic

Utterly fascinating.

LikeLike