London’s gas holders are vanishing. These towering Victorian marriages of form and function have, for several generations, been a distinctive part of the urban landscape. But modern gas networks have rendered them obsolete, and they now stand redundant and vulnerable, occupying valuable land.

While most Londoners would acknowledge the need for new housing, not everyone looks at gas holders with the cold eye of the developer. Many want them to stay. They are admired from trains, gazed at from pavements, campaigned over, documented, repurposed, pulled down and put back up again. They are loved.

Of course, they can be met with indifference, too. But if you stopped your average Londoner and asked them about that hulking great circular relic of the industrial era behind those houses over there, at the very least they’d know what it was. They may call it a gas holder, or a gasometer, or something else, but they’d be able to tell you roughly why it was built. And, 99 times out of 100, they’d be right. Because all of those hulking great things were built to hold gas.

Except for the one that wasn’t.

Henderson’s Door

By the late 1860s Frederick Hercules Henderson was down on his luck. Thirty-nine and unmarried, he was broke. Born of not inconsiderable means, he had invested his money in urban canal shipping, only to see the industry destroyed by the railway boom of the 1840s. He had the air of a man who had been left behind by his century.

But Henderson still enjoyed a degree of social status. His influential friends included the scientist Arthur Longthorn, and thus he was present at the Greenwich Unveiling (more of which in a later blog), the event at which Longthorn showcased his revolutionary ‘Worlds Machine’ to a select gathering, so kickstarting the Victorian interest in inter-dimensional travel. Henderson was far from the only person present at the Unveiling who would become involved in the 19th Century Portal movement. But he was perhaps the only one who saw clearly the popular, commercial potential in what he had witnessed. His pursuit of this potential would eventually devastate his health, end a valued friendship, and financially ruin Henderson for good.

Sadly, the early part of the development of London’s first commercially accessible Portal appears to be undocumented (Henderson feared corporate theft so initial plans were a closely guarded secret). We know, of course, Henderson had concluded that only the constructors of London’s cast-iron gas holders could produce the huge, circular frame he needed. His model even included the customary telescopic ‘frame-within-a-frame’ mechanism. Only it wasn’t a gas container that Henderson’s machine needed to hoist.

At Greenwich, he had witnessed Longthorn harness electricity to create what Henderson referred to as “modest openings in the Kosmos: akin, if you will, to doors that are slightly ajar, facing one another across a dark hallway”. Henderson wanted to throw those doors wide open, and to do this he needed to generate a lot of power. His contraption was designed to hoist a membrane filled with zinc and copper sulphate, and is said to have utilised four miles of wires. It has been described as a giant walk-in battery and electrical circuit in one.

Opened among great fanfare, ‘Henderson’s Door’ was advertised as offering a brief, life-changing vision into the reality of other worlds. ‘Step From This Earth in an Instant!’ proclaimed the posters.

Many took up the offer. Initially, The Door was a great success. Members of the public spoke of visions of ‘impossible worlds’, and of having seen ‘heaven itself, more glorious than I ever imagined’.

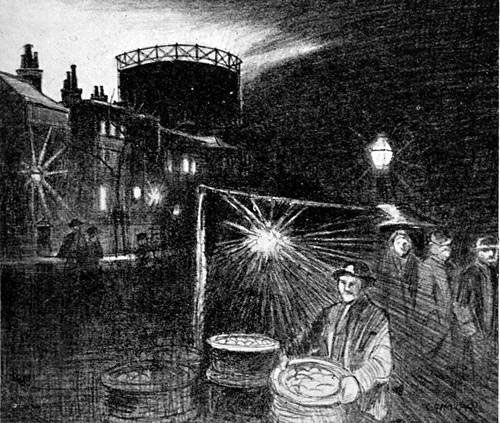

A range of pricing catered for all Londoners. Politicians and other members of high society paid 2 guineas for an hour-long ‘voyage’ on Saturdays, and the working classes queued up for the popular 1 shilling ticket on a Tuesday night. Whatever the occasion, whenever Henderson opened his Door, the surrounding streets would buzz with food stalls, postcard sellers, and others hoping to cash in on the phenomenon.

(The image below, a contemporary drawing, shows a man selling dumplings near Henderson’s Door on ‘poor night’. Note how the Door’s wiring is wound so tight that only a few spots of light shine through. However, light bursts out of the top of the structure. It was said that when active, Henderson’s Door lit up the sky “from Hampstead Heath to the Oak of Honor”)

For a brief moment, Frederick Henderson was the most venerated man in London. But it would not last. Just four months after opening his attraction, Henderson was forced to close it, amid concerns about the safety of the electrical framework.

Opinion had already begun to turn against the project following stories of disappointed punters. Many questioned Henderson’s claim to have opened a door to other worlds. He was accused of hoodwinking a susceptible public with the use of ‘hidden vents’ and lighting tricks.

These claims were leant credence by the fact that, as Henderson himself admitted, not everybody would experience other worlds once walking inside his machine. “I can only open the Door”, said Henderson. “One must step through it oneself”.

A public spat between Henderson and Longthorn didn’t help. Longthorn accused his former friend of stealing his work uncredited and turning it towards ignoble goals.

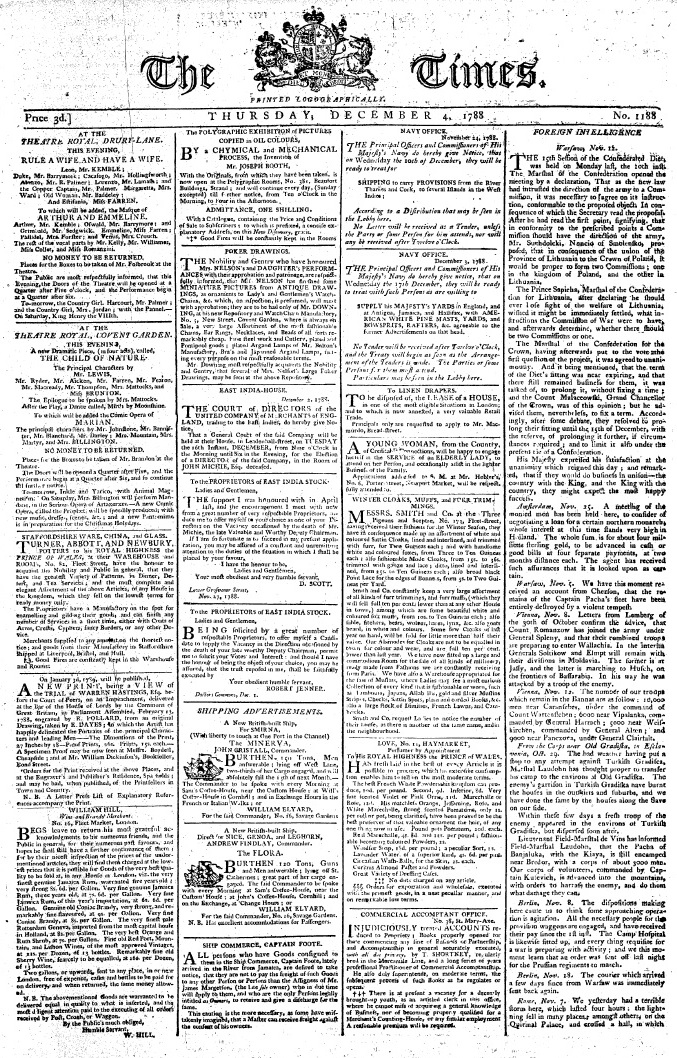

But it was an editorial in the Times of London which perhaps did most to close the Door down (and there are many who detect the hand of Longthorn in its writing):

“…This mountebank, this fraud, this thief. This shameless charlatan. With nothing but the basest contempt for you, my fellow citizens, he would enrich himself by endangering London – and so, by extension, England, for surely our fair land would flail and flounder like a wounded beast were its head to be cut off by the wires and trickery of this vile imposter…”

Henderson went to his grave defending his invention, and he went to his grave early, entering a rapid physical and spiritual deterioration which his contemporaries ascribed to his very public ‘trial’, but which modern scholars believe was caused by a high concentration of dimensional breaches. Nobody walked through Henderson’s Door more often than Henderson himself.

Forgotten now, many books were written about Henderson’s Door in the years after Henderson’s death. But it was the mysterious case of Sam Peech – the Lambeth street urchin who several witnesses recalled walking wide-eyed into Henderson’s contraption during an early test – that provided the subject of the best-selling book on the whole affair: T.P Maudley’s ‘The Boy Who Didn’t Return’.

The disappearance of the gas holders is sad enough. It is happening in towns and cities across Britain. Only when they are entirely gone from our neighbourhoods might we fully understand the connection we had to them.

But if what remains of Henderson’s Door was to go, pulled down by an energy company scratching their heads at the apparent administrative error that led to such a large piece of infrastructure going unrecorded – that would be a shame indeed.

- Candidate: Henderson’s Door

- Type: Interstellar (Unconfirmed)

- Status: Historic

Thanks for a great post! But where exactly is it?

LikeLike