Henrietta Godling, who came from a family of 19th Century timber importers, is sometimes called the first portologist.

As a young woman she had visited the Great Exhibition of 1851 and happened to be present at the Vacuum Sugar Event, at which a window to a celestial realm briefly opened. It sparked a lifelong interest in London’s ‘strange occurrences’.

Though she never used the word ‘portal’, the connections Godling drew between historical events like the House of Hidden Things and the Quaerium inform research to this day.

Godling planned to open London’s first museum on the subject – and might have done, had she not discussed her findings with her cousin, the scientist Arthur Longthorn, and set in train a series of events that would carry her knowledge far from what she had in mind.

We have written before about the Victorian ‘World Door’ movement. Our post on Henderson’s Door details how a vast, electrically-powered portal was undone by a public feud between its creator Frederick Henderson and Longthorn.

That feud had its origins in Longthorn’s own scientific breakthrough, an event widely considered to have kickstarted Victorian interest in London’s volatile temporal borders: the Greenwich Unveiling.

Godling’s research had convinced Longthorn that opening doors between worlds was possible. Longthorn, who had connections in the Royal Navy, knew that theories of time-travel and other interdimensional trickery were of interest to imperial power as well as science. What’s more, he thought he could make those theories a reality.

Armed with technological drawings and (spurious) reports that the Spanish had already built such a device, he secured Navy funding and a small plot at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich.

The proximity to the observatory proved fruitful. Longthorn built a domed structure, and employed telescope makers and engineers to install a mechanism that could direct electrical power across the building’s interior hemisphere.

Longthorn called it his ‘Worlds Machine’, and in November 1869 invited Henderson, Godling, and a handful of others to his Great Unveiling.

What stands out from reports of that night is the very real physical danger the attendees were in. According to Godling, they went into the machine ‘dressed for the Arctic or the deep dark Sea’ – Longthorn provided insulated footwear and clothing, including rubber helmets fitted with thick earmuffs.

As the small crowd stood in a circle in the centre of the building, facing outwards, Longthorn directed a ‘violent and unbridled stream of electricity’ toward the upper part of the room.

It was in the space between the flashes of electrical light and the shadows of the inner-dome that other worlds were glimpsed. Someone thought they saw an ‘impossible city’. Someone else, geological structures like ‘the pocked surface of a distant moon’.

But the vision seen by most of the attendees was a ‘great comet’.

And it is the comet that leads some today to believe they have cracked a long held mystery – where exactly did Longthorn’s Worlds Machine stand?

By 1880 the Navy had lost interest in Longthorn’s ‘impracticable research’. His device – and the building that housed it – was dismantled.

No official details of the Worlds Machine survive. But did the architect of a later observatory leave clues to its location?

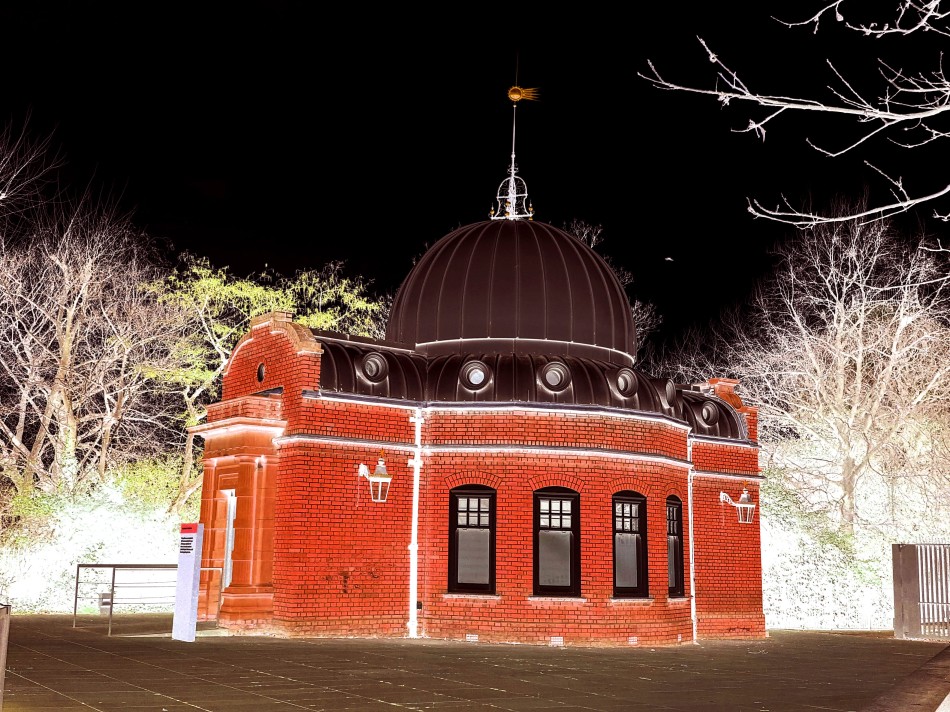

The Altazimuth Pavillion (pictured above) was built in 1899 to house an altitude-azimuth orienting telescope. Today it is home to a science exhibition. And, many believe, stands on Longthorn’s site.

One alleged clue is its porthole design, said to recall the ring of iron apertures around the top of Longthorn’s building, through which thick wires channeled electricity from battery units circling the dome.

Then there is the code which some claim to have found in the brickwork, spelling out Longthorn’s name.

But it is the Pavillion’s comet-shaped weathervane (which dates from 1901 and is fashioned after the Bayeux Tapestry’s depiction of Haley’s comet) that for many is a coincidence too far.

Because attendees at the Greenwich Unveiling didn’t just report seeing a comet. Several of them would become haunted by the vision. One, the artist John Derrick, incessantly drew cosmic scenes for decades after.

Henrietta Godling herself was troubled by visions of the comet for the rest of her life. In her dreams the ‘vaporous rock’ was ‘close to me, in the voidness of space, in the vast, terrible silence, close, and ever-moving in its unknown purpose’.

She became convinced that the comet was part of a continuous thread that went back to what she witnessed at the Great Exhibition. It became hard for her to reconcile this with the fact that, contrary to her expectations, she saw interest in London’s fractious temporal condition wane within her lifetime.

Her headstone bears an inscription taken from James Thomson’s 18th Century poem, The Seasons:

While, through the wilds of barren ether,

They see the blazing wonder rise anew.

- Candidate: The Greenwich Unveiling

- Type: Interstellar

- Status: Historic

While, from his far excursion thro’ the wilds

Of barren ether, faithful to his time,

1720

They see the blazing wonder rise anew,

Lovely! I was puzzled at first by the scansion in the James Thomson quote but verified that there are some words left out. If I can leave out ‘autem’ in ‘tunc autem facie ad faciem‘ (‘but then face to face’) in my quote from St Paul on Nan and Gramps’s memorial stone at Storrington, Godling’s headstone can leave a few words out.

I love the echo of the building in the tapestry depiction of the comet.

Before we moved into the flat to let the builders put in air source heat pump heating at S.C. I was reading Erasmus Darwin’s ‘Loves of the Plants’ (or rather, the second vol which I bought by mistake instead of the first), have you ever read it?

xxx

Emma Tristram

emma@tristram.biz

**PLEASE NOTE THIS IS MY NEW EMAIL ADDRESS, PLEASE UPDATE YOUR RECORDS ACCORDINGLY**

LikeLike

Apparently Henrietta Godling was mildly addicted to blackberry wine and the copy the engravers had to work from was covered in purple stains.

No, I haven’t read ‘Loves of the Plants’. Reading about it now. Volume one sounds good, too!

LikeLike

This is fascinating , thank you for writing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

This is a well-researched article.

I am a local artist-photographer in the early stages of planning my next project (2021-2022) which will be a series of photo inspired by myths of greenwich and blackheath.

I’d love to touch base with you some time and perhaps collaborate in future

Best wishes,

Sarah Garrod

http://www.sarahgarrod.co.uk http://www.facebook.com/sarahGPhotog Insta: @SarahG.Photog Mob: 07885 782371

>

LikeLike

Hi, thanks! Love the work on your website. Hope you can start exhibiting live again soon. Would love to chat. My email is portalsoflondon@gmail.com. You might want to read this article where I discuss my research methods!: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/jan/08/woolwich-foot-tunnel-portals-of-london

Thanks again,

Tom

LikeLike

Didn’t know you was a fan of Scarfolk. Another of my favorite sites.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah yes, it’s brilliant!

LikeLike

Have you considered creating a podcast series?

Your content is so en pointe it deserves a wider audience.

My current favourite is The Magnus Archives but your stories do bring to mind Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman.

Wishing you a fruitful future and many eldritch tale to come.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, glad you like the blog. I have considered a podcast from time to time, but haven’t got much further than that!

I will check out the Magnus Archives, thank you. I’m not familiar with Neverwhere (I’m avoiding it until – if ever – this project is over) but I’m sure Coraline and The Graveyard Book lurk in the crowd of influences.

LikeLike